Abstract

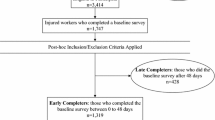

Introduction: This paper reports on the predictive validity of a Psychosocial Risk for Occupational Disability Scale in the workers’ compensation environment using a paper and pencil version of a previously validated multimethod instrument on a new, subacute sample of workers with low back pain. Methods: A cohort longitudinal study design with a randomly selected cohort off work for 4–6 weeks was applied. The questionnaire was completed by 111 eligible workers at 4–6 weeks following injury. Return to work status data at three months was obtained from 100 workers. Sixty-four workers had returned to work (RTW) and 36 had not (NRTW). Results: Stepwise backward elimination resulted in a model with these predictors: Expectations of Recovery, SF-36 Vitality, SF-36 Mental Health, and Waddell Symptoms. The correct classification of RTW/NRTW was 79%, with sensitivity (NRTW) of 61% and specificity (RTW) of 89%. The area under the ROC curve was 84%. Conclusions. New evidence for predictive validity for the Psychosocial Risk-for-Disability Instrument was provided. Implications: The instrument can be useful and practical for prediction of return to work outcomes in the subacute stage after low back injury in the workers’ compensation context.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Volinn E, Van Koevering D, Loeser JD. Back sprain in industry: The role of socioeconomic factors in chronicity. Spine 1991; 16: 542–548.

Spitzer WO, LeBlanc FE, Dupuis M. Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity-related spinal disorders: A monograph for clinicians. Report of the Quebec Task Force on spinal disorders. Spine 1987; 12: S1–S59.

Reid S, Haugh LD, Hazard RG, Tripathi M. Occupational low back pain: Recovery curves and factors associated with disability. J Occup Rehabil 1997; 7: 1–14.

Webster BS, Snook SH. The cost of compensable low back pain. J Occup Med 1990; 32: 13–15.

Hashemi L, Webster BS, Clancy EA, Volinn E. Length of disability and cost of workers’ compensation low back pain claims. J Occup Environ Med 1997; 39: 937–945.

Williams DA, Feuerstein M, Durbin D, Pezzullo J. Health care and indemnity costs across the natural history of disability in occupational low back pain. Spine 1998; 23: 2329–2336.

Main CJ, Burton AK. Economic and occupational influences on pain and disability. In: Main CJ, Spanswick CC, eds. Pain management: An interdisciplinary approach. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston, 2000, pp. 63–87.

Kendall NAS, Linton SJ, Main CJ. Guide to assessing psychosocial yellow flags in acute low back pain: Risk factors for long-term disability and work loss. Wellington, New Zealand: Enigma, 1997.

Kendall NAS. Psychosocial approaches to the prevention of chronic pain: The low back paradigm. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol 1999; 13: 545–554.

Black C, Cheung L, Cooper J, Curson-Prue S, Doupe L, Guirguis S, Haines T, Hawkins L, Helmka S, Holness L, Levitsky M, Liss G, Malcolm B, Painvin C, Wills M. Injury/illness and return to work/function: A practical guide for physicians. Retrieved from http://www.wsib.on.ca/wsib/wsibsite.nsf/LookupFiles/DownloadableFilePhysiciansRTWGuide/$File/RTWGP.pdf: March 5, 2001.

Carter JT, Birrell LN. Occupational health guidelines for the management of low back pain at work—principal recommendations. Retrieved from http://www.facoccmed.ac.uk/BackPain.htm: March 2000.

Main CJ. Concepts of treatment and prevention in musculoskeletal disorders. In: Linton SJ, ed. New avenues for the prevention of chronic musculoskeletal pain and disability. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2002, pp. 47–63.

Boersma K, Linton SJ. Early assessment of psychological factors: The Örebro Screening Questionnaire for pain. In: Linton SJ, ed. New avenues for the prevention of chronic musculoskeletal pain and disability. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2002, pp. 205–213.

Linton SJ, Boersma K. Early identification of patients at risk of developing a persistent back problem: The predictive validity of the Örebro musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire. Clin J Pain 2003; 19: 80–86.

Waddell G, Burton AK, Main CJ. Screening to identify people at risk of long-term incapacity for work. London: Royal Society of Medicine, 2003.

Hazard RG, Haugh LD, Reid S, Preble JB, MacDonald L. Early prediction of chronic disability after occupational low back injury. Spine 1996; 21: 945–951.

Gatchel RJ, Polatin PB, Kinney RK. Predicting outcome of chronic back pain using clinical predictors of psychopathology: A prospective analysis. Health Psychol 1995; 14: 415–420.

Nordin M, Skovron ML, Hiebert R, Weiser S, Brisson PM, Campello M, Harwood K, Crane M, Lewis S. Early predictors of delayed return to work in patients with low back pain. J Muscul Pain 1997; 5: 5–27.

Linton SJ, Halldén K. Risk factors and the natural course of acute and recurrent musculoskeletal pain: Developing a screening instrument. In: Jensen TS, Turner JA, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, eds. Proceedings of the 8th World Congress on Pain, Progress in Pain Research and Management, Vol. 8. Seattle, WA: IASP, 1997, pp. 527–536.

Linton SJ, Halldén K. Can we screen for problematic back pain? A screening questionnaire for predicting outcome in acute and subacute back pain. Clin J Pain 1998; 14: 209–215.

Harper AC, Harper DA, Lambert LJ, de Klerk NH, Andrews HB, Ross FM, Straker LJ, Lo SK. Development and validation of the Curtin Back Screening Questionnaire (CSBQ): A discriminative disability measure. Pain 1995; 60: 73–81.

Crook J, Milner R, Schultz IZ, Stringer B. Determinants of occupational disability following a low back injury: A critical review of the literature. J Occup Rehabil 2002; 12: 277–295.

Sullivan MJL, Stanish W, Waite H, Sullivan M, Tripp DA. Catastrophizing, pain, and disability in patients with soft-tissue injuries. Pain 1998; 77: 253–260.

Hurley DA, Dusoir TE, McDonough SM, Moore AP, Linton SJ, Baxter GD. Biopsychosocial Screening Questionnaire for patients with low back pain: Preliminary report of utility in physiotherapy practice in Northern Ireland. Clin J Pain 2000; 16: 214–228.

Feuerstein M, Berkowitz SM, Haufler AJ, Lopez MS, Huang GD. Working with low back pain: Workplace and psychosocial determinants of limited duty and lost time. Am J Ind Med 2001; 40: 627–638.

Nunnally JC, Jr. Introduction to psychological measurement. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1970.

Schultz IZ, Crook JM, Berkowitz J, Meloche GR, Milner R, Zuberbier OA, Meloche W. Biopsychosocial multivariate predictive model of occupational low back disability. Spine 2002; 27: 2720–2725.

Sandström J, Esbjörnsson E. Return to work after rehabilitation: The significance of the patient’s own prediction. Scand J Rehabil Med 1986; 18: 29–33.

Cole DC, Mondlock MV, Hogg-Johnson S. For the Early Claimant Cohort Prognostic Modelling Group. Listening to injured workers: How recovery expectations predict outcomes—a prospective study. Can Med Assoc J 2002; 166: 749–754.

Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) 1. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30: 473–483.

Karasek R, Kawakami N, Brisson C, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol 1998; 3: 322–355.

Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy work—stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. New York: Basic Books, 1990.

Schultz IZ, Crook J, Meloche GR, Berkowitz J, Milner R, Zuberbier OA, Meloche W. Psychosocial factors predictive of occupational low back disability: Towards development of a return to work model. Pain 2004; 107: 77–85.

Campbell DT, Fiske DW. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol Bull 1959; 56: 81–105.

Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and stadardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess 1994; 6: 284–290.

Gatchel RJ, Polatin PB, Noe C, Gardea M, Pulliam C, Thompson J. Treatment- and cost-effectiveness of early intervention for acute low-back pain patients: A one-year prospective study. J Occup Rehabil 2003; 13: 1–9.

Feuerstein M, Thebarge RW. Perceptions of disability and occupational stress as discriminatory of work disability in patients with chronic pain. J Occup Rehabil 1991; 1: 185–195.

Frymoyer JW. Predicting disability from low back pain. Clin Orthop 1992; 279: 101–109.

Cheadle A, Franklin G, Wolfhagen C, Savarino J, Liu PY, Salley C, Weaver M. Factors influencing the duration of work-related disability: A population based study of Washington state workers’ compensation. Am J Public Health 1994; 84: 190–196.

Engel CC, Von Korff M, Katon WJ. Back pain in primary care: Predictors of high health-care costs. Pain 1996; 65: 197–204.

incus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, Field AP. A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine 2002; 27: E109–E120.

Pulliam CB, Gatchel RJ, Gardea MA. Psychosocial differences in high risk versus low risk acute low back patients. J Occup Rehabil 2001; 11: 43–52.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schultz, I.Z., Crook, J., Berkowitz, J. et al. Predicting Return to Work After Low Back Injury Using the Psychosocial Risk for Occupational Disability Instrument: A Validation Study. J Occup Rehabil 15, 365–376 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-005-5943-9

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-005-5943-9